Andy and Natalie’s mission emphasizes the importance of Tennessee’s plants historically and now.

Distinguished Lecturer Andy Pulte and Associate Professor Natalie Bumgarner of the Department of Plant Sciences at the University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture spent much of 2018 developing Ten Plants That Shaped Tennessee. More than 600 nominations were submitted, and submissions were open to the public. Together with a panel of other UTIA experts in a range of fields, all nominations were weighed, and each nomination’s significance was carefully considered to develop the final list of 10 plants that most influenced the state. At the heart of the project is a love of Tennessee and a desire to communicate the importance of plants for everyone.

Explore the List

Carol Reese, UT Plant Sciences research specialist, talks about the importance of the almost extinct American Chestnut to the Appalachian region.

It has been nearly eighty years since the “King of the Forest” was deposed in Tennessee. A lethal fungal blight that attacked the vital nutrient transport systems of the mighty American chestnut tree came to the US on imported trees in 1904. By the 1940s, the pathogen had marched through the native range of the American chestnut where it killed trees from the stump up. Since this invasive pathogen didn’t kill the roots, young sprouts from remaining root systems sometimes appear briefly as a reminder before themselves being killed.

A man stands next to an American chestnut in Mitchell County, North Carolina in 1914. Photograph courtesy of the United States Forestry Service.

The widespread and majestic tree so valued for timber and wildlife has been gone from our forests for decades. American chestnut’s native range in the eastern United States was from Maine to Mississippi, which constituted more than 200 million acres. Within this area, it is estimated that 4 billion trees could have been present.

The story of American chestnut (Castanea dentata) is one that tells a story of ecological change across a region. In this case, nonnative pests were inadvertently introduced, for which the native species had no defense. Breeding has been ongoing for decades to bring resistance from Chinese chestnut to our American species to provide protection against the blight and restore this species to its native range. Many different aspects of this breeding program exist, and work takes place using both public and private funding.

The UT Institute of Agriculture is currently playing a part in the American chestnut story through interacting with federal researchers. The ultimate success of these extensive breeding efforts are still unknown, as widespread reintroduction of chestnut to native forests still appears to be in the future. While maybe the most well-known example of an invasive pest, chestnut blight is certainly not the only pest or disease that has been or is impacting forests in Tennessee. But, it does serves as a stark reminder of the potential impact of introduced pathogens.

UTIA does research reintroducing chestnuts to Tennessee forests.

Angela McClure, UT Plant Sciences professor, talks about one of Tennessee’s most notable modern crops – soybeans.

If you have any doubt that beans have played a key role in shaping Tennessee, then maybe you should try to convince a longtime gardener in the state to replace their favorite pole bean with a modern bush snap bean. Their likely rapid and emphatic response will provide a glimpse into the role of beans in culture and history across the state.

Workers pick beans on the Mounts Brothers Farm, Mountain City, Tennessee, in 1942. Photograph courtesy of United States Department of Conservation Photograph Collection.

Native Americans grew this vegetable long before European settlers cultivated beans in Tennessee. They used it in their Three Sisters planting system along with squash and maize (corn). Today, family lines of beans are passed down through generations, and seedsman across the region and country have caught on to the culinary benefits and cultural richness of beans like ‘Turkey Craw’ and ‘Lazy Housewife’. A quick online search will provide you the opportunity to grow a tasty legume like ‘Greasy Grits’ that has long been a part of Appalachian history.

Beans (Phaseolous vulgaris) aren’t just a historical or hobby crop in Tennessee. Snap bush beans are grown in quantity on the Cumberland Plateau, making the state the number 11 and number 13 in fresh and processed snap beans in value in 2017.

Even with this snap bean production, any current agricultural producer will tell you soybeans (Glycine max) are the most economically impactful bean in Tennessee today. Around the 1950s, soybeans went from the new bean in town to a cornerstone of Tennessee’s agricultural economy with about a thousand-fold increase in production between 1949 and 1992. Soybeans now provide more than 20 percent of Tennessee’s farm gate receipts, and are the most valuable commodity in our agriculture system, topping even corn, cotton, and cattle.

The UT Institute of Agriculture’s Department of Plant Sciences is home to a breeding program that excels in turning out new and productive soybean cultivars, whose products support animal production and industrial products along with the human diet.

Beans are not only a favorite at Tennessee dinner tables but also an important economic staple.

Virginia Sykes, UT Plant Sciences assistant professor of agronomy, explains that corn will, in fact, grow on Rocky Top!

Perspectives on the role corn has played in shaping Tennessee can be surprisingly varied across the state. West Tennessee residents might view it mainly as an agronomic centerpiece. And they would be correct because it holds the position of the number 4 most valued crop sold from Tennessee farms. With a current footprint between 750,000 acres and 1 million acres annually, corn (Zea mays) is a well-known sight from interstates and one-lane roads alike across crop-producing areas. In Middle Tennessee, it is likely corn will be tied historically to William Haskell Neal, who bred two-ear Paymaster corn around 1900, changed the face of Tennessee agriculture and agronomy for years to come. In East Tennessee, corn may conjure images of grits and cornpone that were dietary staples along with stories of stills and ’shine.

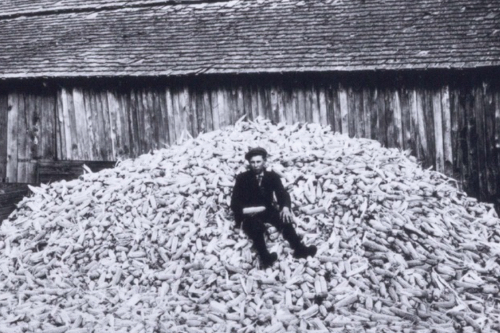

A 4-Her sits atop his prize corn in 1912. Photograph courtesy of Elsie Carper Collection on Extension Service, Home Economics, and 4-H.

In reality, the role of corn in shaping Tennessee weaves together these regional stories. It has likely been a staple plant in the state for as long as humans have been growing crops here. Native to present day Tennesseans have used corn as a grain for human and animal diets, and have grown it to produce everything from moonshine to Coca Cola (corn syrup) to shuck-filled mattresses.

Production volume and geography of the crop have changed through the years. Corn was often the first crop planted by settlers and could be found on hillsides growing between freshly cleared stumps in the 1700s. In the 1800s and early to mid-1900s, commercial corn production was heavily practiced in Middle Tennessee. In fact, in 1840, Tennessee was the highest corn producing state in the country.

Corn value has fluctuated over the years in comparison to other crops. Breeding advances and fertilizers increased yields throughout the twentieth century. These and other changes, including the flooding of fertile river bottoms used for crop production in parts of Tennessee, pushed large corn growing areas westward. Today, the majority of Tennessee’s corn production is in West Tennessee, where it remains a cornerstone of agriculture.

Corn remains culturally important and an agronomic staple in Tennessee.

Tyson Raper, UT Plant Sciences assistant professor, explains cotton’s prevalence in West Tennessee. Bonus: drone footage taken by Dr. Raper’s former graduate student Shawn Butler!

If you live in Tennessee’s Crockett or Haywood Counties or the surrounding area, you know what a sight fall fields of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) can be. Although there has been some cotton production in other parts of the state in decades past, West Tennessee is where the action is now when it comes to growing cotton. Large-scale cotton production began in our state in the 1820s with production growing to over a million acres in a century.

Cotton is heavily associated with the fields of West Tennessee.

The history of cotton in Tennessee and other southern states is complex because it is intertwined with a cultural, racial, and economic structure that defined and impacted agriculture and society across many generations. Pre-Civil war, cotton was a principal cash crop often grown year after year on the same deep fertile land. Growing and raising cotton before widespread mechanization required a lot of hand labor, and the crop was most often worked by slave labor on large plantations. This gave way to a sharecropping system to provide labor after emancipation, which often left farm workers with little ability to better their lives outside of relocation. In 1931 the famous Memphis Cotton Carnival was founded to help promote the use of cotton and bolster the region during the Great Depression.

Currently, over 300,000 acres of our state are devoted to cotton production yearly. Cotton is a food and fiber crop. Its fiber is used in virtually every type of clothing and its seed is crushed for oil and meal, which is used to feed livestock and for food products. Cotton and its production are important to our state for its economic, social, cultural, and historical significance.

Andrew Pulte, UT Plant Sciences distinguished lecturer, talks about a most prized plant.

Spring would not be spring in Tennessee without the bloom of the dogwood. On its bare branches, flat blooms shine like stars across the hillsides, parks, and lawns of our state. Found naturally across many Tennessee counties, Cornus florida, or flowering dogwood, is one of the most beautiful small trees around, bringing ornamental value to our landscape four seasons of the year.

A group of tourists enjoy dogwood trees in the Smoky Mountains in 1953. Photograph courtesy of United States Department of Conservation Photograph Collection.

Native across the Eastern seaboard, dogwood is a plant beloved and known by even the newest of naturalists and gardeners. Additionally, dogwood benefits our Tennessee wildlife. Squirrels, cedar waxwings, cardinal, mockingbird, robin, and turkey all feed on its bright red fruit in the winter.

Historically, the dogwood’s reputation for beauty spans the globe. In 1912, the mayor of Tokyo, Japan, sent 3,000 cherry trees as a gift to Washington, DC. Three years later, the US reciprocated with a gift of flowering dogwood trees.

In early American history, dogwoods also were valued for their wood, which was of economic importance. A hard, close-grained, tough wood, dogwood was once employed for making shuttles in the textile industry (weaving). Textile manufactures found that the longer a dogwood shuttle was in use, the smoother its wood became. Dogwood logs were sent as far as England to support production in textile mills.

Today, flowering dogwood is also of economic importance to Tennesseans. In nursery production, which centers in Middle Tennessee, our state ranks first in dogwood production. And at the UT Institute of Agriculture, many new disease resistant dogwoods now common in the industry are from the UTIA breeding program. In addition to being a nursery staple, dogwoods also drive tourism in our state. Several annual celebrations and festivals across the state coincide with dogwood bloom. In 2018, former governor Bill Haslam proclaimed April 21 as Tennessee Dogwood Day. This new proclamation recognizes dogwoods as an important tree across our state.

Dogwoods are celebrated across Tennessee.

In Appalachia, whether historically or in present day, there are few truer signs of trust and kinship than sharing the location of someone’s personal or family ’sang patch. Part economy, part culture, part history, the tale of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) in East Tennessee and across the rest of the eastern deciduous forests where the plant is native is complex.

Tillman E. Lee of the Soil Conservation Service and Fred Markus observe ginseng seed pods on Markus’ farm in Lawrence County, Tennessee, in 1966. Photograph courtesy of the United States Department of Conservation Photograph Collection.

This native herbaceous perennial plant has been harvested and used or sold for hundreds of years. The North American species has long held a place in Native American medicine. When European settlers began arriving in the region, it didn’t take long to connect the American Panax with related species highly valued in Asian medicine. Following this discovery early in the 1700s, ginseng became an export crop whose harvest was practiced or noted by historical figures from Daniel Boone to George Washington.

Wild harvest of American ginseng, known as “ginsenging” still exists in the Appalachians much as it has for generations. In the forest itself, the growth and productivity of ginseng offers confirmation of a healthy ecosystem. However, these slow-growing populations are constantly under pressure from harvesting for sale, as production of wild simulated ginseng has not been widely successful. Wild harvest is legal on private land, but illegal poaching is an ever-present issue on public lands, such as the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, where family ginseng patches may well pre-date the existence of the park itself. It is this intriguing mix of botany, ecology, history, culture, and medicine that place American ginseng on the list of the ten plants that shaped Tennessee.

“Gensinging” is a Tennessee pastime and lucrative activity.

Gary Bates, UT Plant Sciences professor and director of UT Beef and Forage Center, speaks to the advantages of grasses, especially the forage tall fescue.

Did you know that corn, wheat, rice, sugarcane, and many other of the world’s most important plants are all types of grass? This selection gives credence to both ancient and modern grass systems that have been and continue to be vitally important to our state.

Wick Knight looking at a fescue and white clover pasture in Lafayette, Macon County, Tennessee. Photograph courtesy of the United States Department of Conservation Photograph Collection.

Only scraps and shadows remain of numerous diverse prairie grass plant communities in Tennessee. Many of us might imagine that the southeastern US was unbroken forest from the eastern seaboard all the way to the prairies of the Great Plains. This is simply not the case. Tennessee was once a complicated mosaic of different types of plant communities, which included forest and some of the most diverse prairie systems on the planet. Bison once roamed these prairies, and Native Americans pursued them and their movements across the state.

While these prairie grass systems are now much less extensive than they once were, grasses managed for grazing are still a key component of Tennessee economy and culture. Across much of East and Middle Tennessee, pasturelands support a cattle and calf agriculture system that produces the second most valuable Tennessee product in farm gate sales. Sustainably managing these pastures of native and introduced forage species connects the field of plant science and animal science to support the beef industry of the state.

It isn’t just farmers who carefully manage grasslands, though. The grass systems that surround our houses and urban environments are what we now think of when we hear “grass, lawn, or yard.” The idea of the “lawn” did not get a substantial start until after World War II with the birth of the suburbs. However, it has become an integral part of our lives. The estimated acreage of turfgrass in Tennessee is somewhere upward of 1 million acres, which is not far off of how many acres of corn and soybeans are planted respectively each year. While our lawns provide a place to enjoy recreation with our families, these spots of greenery also provide ecosystem services like filtering water and converting carbon dioxide into oxygen.

Grasses are one of the largest contributors to Tennessee’s agricultural economy.

Chris Cooper, Shelby County UT Extension agent and host of East Tennessee PBS The Family Plot, reveals the vine that ate the South.

Since before we called this country America or this state Tennessee, exotic species have poured into this land. So much so that few Americans can tell you which plants and animals might have been here before European settlement. Each one of these plants or animals has a story to tell that echoes something about who we are as a society. While some whisper their stories, others shout them from the rooftops, or more literally hillsides.

Kudzu held the soil in this large gully located near Jackson, Tennessee, in 1941. Photograph courtesy of the United States Department of Conservation Photograph Collection.

Kudzu (Pueraria montana var. lobate) is just one of those plants. It was introduced to Americans as a potential miracle vine at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876 when its nature was not fully known. Kudzu was slow to catch on; it was not easy to propagate and heavy grazing by livestock seemed to damage it severely. However, it did perform a kind of sinister rescue in our state and across many parts of the South by stabilizing deep scars on hillsides as railroad transportation cut across the continent and providing surface cover for eroded soils caused by poor farming practices.

Kudzu is not the most invasive plant in Tennessee, nor is it the most economically damaging. However, it is a plant that most Tennesseans can recognize, and few who call the state home are without an opinion of the vine. It plays a very important role in bringing awareness to the protection of our natural environment. Any young person can look at the sculptures created by kudzu on the side of the road and realize that something is not quite right. Kudzu can be used as a lens we all look though to help understand how species interact with each other and the interconnectedness of species on this planet.

Kudzu covered hillside are now an iconic reminder of the importance of limiting soil erosion.

For those raised in a tobacco-producing regions, there are fewer agricultural sights more imprinted in their memories than tobacco hung layer upon layer in barns as it dries in the fall.

A worker cuts dark-fired tobacco in Robertson County, Tennessee, in 1946. Photograph courtesy of the United States Department of Conservation Photograph Collection.

In Tennessee, there are regional differences in the types of tobacco grown. Burley tobacco is air dried and is grown in both East and Middle Tennessee, although the East Tennessee burley regions are likely the most famous. In parts of Middle Tennessee, especially around the Highland Rim, a type called dark-fired grows in fields in addition to burley. After harvest, white wisps of smoke ascend from roofs of barns as a part of the curing process for the aptly named dark-fired tobacco. Many a tale from newcomers to the region includes calling the local fire department in error, trying to save the barns of their farming neighbors.

The story of tobacco in shaping Tennessee is not an easy one to tell because it comes with both human benefit and loss. Tobacco was one of the earliest crops planted by settlers in Tennessee and has long supported farmers and agricultural communities in the state. The epicenter of the burley tobacco production revolution was in Greeneville, in East Tennessee. In fact, many of the most commonly grown cultivars of burley were bred at UT Institute of Agriculture research facilities in the area. As recently as the late 1990s, tobacco was the most highly valued crop in Tennessee, often outpacing soybeans and corn in cash receipts.

Early in this century, changes to the regulations allowing the production of the crop shifted the entire paradigm of tobacco production in Tennessee and many other US states. What’s more, health implications associated with tobacco-based products, legal decisions affecting large corporate buyers of the crop, and geographical changes in production globally have all contributed to a decline in the acreage and economic value of tobacco in Tennessee today.

Tobacco has a complicated history in Tennessee.

David Mercker, UT Forestry, Wildlife, and Fisheries Extension Specialist, talks about an abundant tree in Tennessee forests.

The oak family is an important component of the forestlands of Tennessee. Many oak species provide both wildlife and humans with an abundance of resources. “If Oak is the king of trees, as tradition has it, then the White Oak (Quercus alba), throughout its range, is the king of kings,” wrote Donald Culross Peattie in his 1950 book on the natural history of trees. The white oak’s range stretches across our state and is a major component of our woodlands and our history.

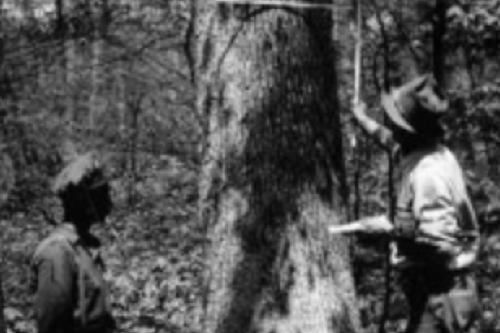

Two men examine a white oak for harvest.

Some of the biggest white oaks in Tennessee are more than 100 feet high and wide. This species of tree is long-lived. Some white oaks in our country were alive when Christopher Columbus left Spain on his first voyage. As long as people have lived in Tennessee, they have been relying on white oaks for survival and income. Wood from the tree is used to build houses and grace hearths as fuel on cold winter nights. The staves, or sections of wood that make up a whiskey barrel, are best made from white oak, and impart a unique taste to whiskey that is distinctively American.

Between 1880 and 1920 Tennessee had a great extraction of timber across the state, providing a hungry nation with the raw materials it needed. This era brought jobs and people to our state. Memphis was once known as the “hardwood capital of the world” and thirty to forty sawmills were scattered across the Mid-South. It was big business and white oak was one of main players. Even today, Tennessee often ranks near the top of hardwood production as forestry continues to be an important but often little recognized economic contributor to Tennessee.

The white oak has served Tennesseeans well.